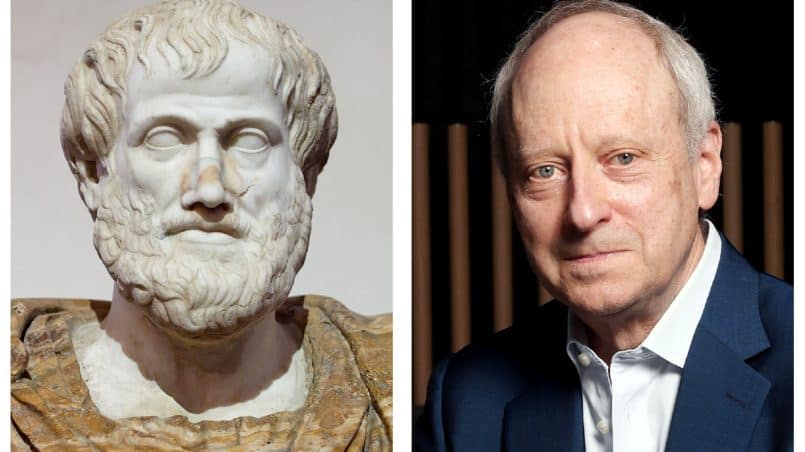

In his book, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?, Michael Sandel examines modern moral theories and finds them all insufficient to account for how and why we make the moral judgments that we do today. Sandel attempts to restore a version of Aristotle’s virtue ethics that is more robust and adapted to our modern world. The result is a theory of morality that calls us to identify the narratives in which we find ourselves, to engage with our community (family, social, religious, national, etc.), and to reflect on what are our duties as members of our community–for the purpose of cultivating our characters. It is a form of civic republicanism that is culturally contextual but not relativistic.

I created the following table to represent the various theories and philosophers Sandel engaged with, and how his views compare.

According to Michael Sandel, utilitarianism fails because it reduces morals to calculations of happiness or welfare, and these calculations lack a qualitative aspect. For example, cold calculations could justify a large majority group oppressing and abusing a small minority group because the overall happiness count of the majority group could remain high. Libertarianism fails because it reduces everything to choice and consent while different people are faced with very different types of choices. For example, a poor person may have to decide between selling one of his kidneys or working in a very dangerous work environment to provide food for his family. According to libertarian principles, as long as this person is not coerced or forced to choose one of these options, his consent makes the situation just.

Like libertarians, Immanuel Kant believed very strongly in freedom, yet his reasoning brought him to an entirely different picture of justice. Kant believed that as rational beings, humans must free themselves from the compulsions of passions and desires by using pure reason. In fact, as paradoxical as it may sound, exactly because we are free, we have a duty to follow our own reasoning. John Rawls, a modern American philosopher, was inspired by Kant’s principles (something utilitarianism lacked), and developed them further using the metaphor of a “veil of ignorance.” A choice is just, argued Rawls, if people could agree on the terms of the choice as if behind a veil of ignorance not knowing whether either one would end up in real life or on either side of the deal. In this sense, libertarianism, Kantianism, and Rawlsianism are all examples of freedom-based theories of justice.

Michael Sandel argues, however, that all of these freedom-based theories lack something important: an end goal, or telos, as Aristotle would say. Instead, we have to reason together about the meaning of the good life. The liberal neutrality that emerged out of the Enlightenment does not lead us to question or challenge the preferences and desires we bring to public life. It taught us not to value people’s preferences because that is being judgmental. But, Sandel says, “justice is inescapably judgmental.” By trying to avoid being judgmental, we have created a society in which individuals are not challenged to be “good.”