Are you studying Ancient Greek? Feel lost? Feel confused? Did you think you were pretty smart, but are now doubting yourself?… I understand. Please, believe me, it’s not your fault. Here’s a list of just a few things that make Ancient Greek so hard. If you haven’t started studying it yet but want to, consider yourself warned!

- First of all, the word order is dizzying. It’s very different than English. One example of a totally bizarre phenomenon is that when two phrases are joined with a conjunction, the conjunction can appear after the first word of the second phrase. For example, you might come across something like, “The man went to the market he and bought some bread.” What?? Who speaks like that? Well, maybe that’s just because we’re used to English word order and should give Ancient Greek another chance. OK, let’s go on…

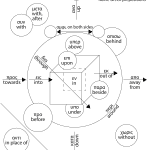

- Ancient Greek is a highly inflected language, which means that spellings of words change based on the way they are used, like “run” and “ran.” Nouns and verbs are created by adding additional words and letters to stems in order to expression number, gender, tense, etc. But the biggest difficultly is that these additional words and letters have a super complex morphology, which means that the letters change when you join them together, making it difficult to recognize exactly which letters were joined where.

- There are six “principal parts” of verbs. In other words, for each verb there are up to six different verb stems, and that doesn’t include the formatives/markers of the different tenses (i.e. augmentation, reduplication, tense formatives/markers, etc.)

- There are two types of aorist verbs — 1st aorist and 2nd aorist — that don’t change anything about the meaning at all. They just exist to make the aorist tense more difficult.

- Personal endings for Koine Greek verbs (1S, 2S, 3S, 1P, 2P, 3P) are absolutely ridiculous. Instead of having a total of six simple endings, Ancient Greek has one set for the active voice and one set for the middle voice, which brings us to 12 different endings. And these two groups also have primary and secondary versions that hardly relate to each other, which brings us to 24 different endings. And then there are variants for active subjunctive, active optative, mi-verbs, PLUS a bunch of irregularities specifically for secondary active 1S and 3P. It’s so ridiculous you literally can’t even count all of the possible personal endings without some debate (particularly because it depends on how you count the connective vowels).

- In English we have two “voices” for verbs: active (“I hit”) and passive (“I was hit”). Koine Greek has three voices: active, middle, and passive — but only sometimes. You see, present, imperfect, and perfect tenses have only two voices: active and… and.. what? Well, grammarians say maybe this second voice could be middle or could be passive. Nice. That’s helpful (sarcasm). But do you want to know the worst thing about Ancient Greek “voices,” the thing that gives you migraines when you all you want to do is enjoy some peaceful reading before bed? It’s that the aorist passive tense uses active personal endings. I think they did this so they could speak in code to each other and no one else could understand what they were saying. Maybe the Ancient Greeks were a bunch of spies. 🥸

- Ok, so what about nouns? Unfortunately, my friends, nouns are just as crazy as verbs. Greek has three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. That in itself is not so bad, right? Some other languages have three genders. But then there are also declensions in Koine Greek that don’t correspond to the genders. How nice it would be if all 1st declension nouns were feminine, all 2nd declension were masculine, and all 3rd were neuter. But nooooooooo. Let’s just mix everything up so you can’t tell which gender a noun is just by looking at it! 🤬

- Not only does Ancient Greek have three genders, but it also has three “numbers.” In most languages around the world, there are two ways to express “numbers” of nouns: singular and plural. But in Ancient Greek there are three: singular (one item), dual (two items), and plural (three or more items). (The one good news for students of Koine or New Testament Greek is that the dual fell out of use by this time.)

- Then there are a few noun case endings that look exactly like some personal endings for verbs making it difficult for the beginning Greek student to distinguish between just what is a freaking verb, and what is a freaking noun! (This list is growing so exhaustive, I’m just not even going to mention the five different cases of nouns. No! I’m just too tired!)

- And then there are participles. What’s a participle, you ask? Participles are verb roots that are modified to function as adjectives or nouns, etc. English has participles too, but the difficulty with Greek participles that is not found in English is that Greek participles: 1. have their own forms (ντ, ντσ, μεν, etc.) that have to be learned separately from both verb forms and noun forms (English participles are formed in more familiar ways) and 2. can still function as verbs. In other words, you could take any simple sentence and express it with either a verb or a participle for the same meaning. Having to learn “two systems of verbs” is required since Greek uses participles so frequently like this. (I’d like to talk to the dude who invented this language.)

- Some languages have a few different variations for the word “the” depending how it is used in the sentence. For example Portuguese has “the” for masculine (“o”) and “the” for feminine (“a”). It can also combine the definite article with the words “of” and “by” to express “of the” (“do,” “da”) and “by the” (“pelo,” “pela”). So in Portuguese there are six different ways to say “the.” You think that’s a lot? Phhhhsstt… that’s nothing. Greek has a word for “the” for three genders, three numbers and four cases of nouns!! Multiply that up. I dare you! Yes, that’s right: 36 ways to say “the”! Who would have thought you needed 36 ways to say “the”?…Yeah, those ancient guys did.

- I could go on, but I must stop for the sake of my own sanity!

My friend Luke Ranieri created a hilarious and educating video that examines even more complexities of Ancient Greek. Watch this video and subscribe to his channel if you haven’t already.

So now you know why I hate Ancient Greek… OK, I’m kidding. I ❤️ Ancient Greek.

What do you find most difficult about Ancient Greek? Tell us in the comments below.

For me it’s the (understandable) lack of graded AG-only reading resources in AG. After a course or two you pretty much have to jump right into texts written at an adult (sometimes very advanced adult!) level. With a living language you can slowly ramp up from early readers to young adult to adult as your reading level in the language grows. Not an issue if you’re learning by translation but definitely one if you’re trying to learn AG like a living language. Also the pronunciation system war. Makes it that much harder for everyone. But like you I love Ancient Greek. 🙂